|

|

National Natural Protected Areas in Hungary |

|

|

|

- Cave Lands - |

|

|

|

The Aggtelek National Park

The various parts of the national

park land were formed in different, rather distant geological

periods. The history of their geological evolution has been

different. They reached their present location in the Cainozoic

era as a result of horizontal movements triggered by tectonic

forces. The ground rock in most of the territory was formed about

230 million years ago in the Triassic period of the Mesozoic era.

It is the characteristic of theses rocks that determine the

features of the landscape, and because of these the region’s

world-famous caves and other karst formations first saw daylight.

Such formations, as well as some other rock associations and

their explorations that now serve as key geological sections,

are unique in Hungary.

The present

form of the Aggtelek Karst Region is basically the result of

karst phenomena and processes related to the destruction of the

limestone ground rock. Nearly all the typical phenomena of

temperate zone karstification, that began in the Ice Age and have

occurred ever since, can be found here in a relatively small

area. However, besides natural forces, human activity has also

played its role in shaping landscape.

In some areas which were once forested, the trees dissolved the milestone lying beneath the topsoil by acids emanating from their roots, and thus created tube-like holes in the ground. Deforestation and the ensuing agricultural utilisation of the land opened the door for precipitation to erode the soil unhindered. The ground rock was thereby revealed, and the remnants of the vegetation left in its tiny cavities (the so-called ‘root karrs’) gradually decomposed. This rugged, riddled and barren surface is called ‘karr’ or in folk terminology the ‘devil’s poughland’. The most beautiful example of such a karr formation is hillside of Tóhegy (Lake Hill), located just above Aggtelek. The national park is a genuine open/air museum of surface karst phenomena. The wooded plateaux are dotted with holes like a piece of cheese: these are sink holes as well as dolinas, where the ceiling of a dissolved hollow collapsed. At some places the remains of karst ravines and collapsed former caves stretch among the limestone blocks.

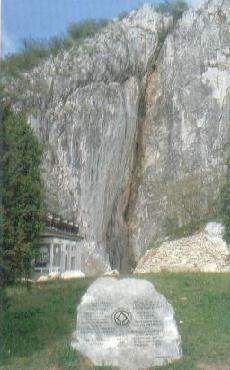

The natural opening of the Baradla Cave at

Aggtelek, with the plaque confirming the World Heritage satus.

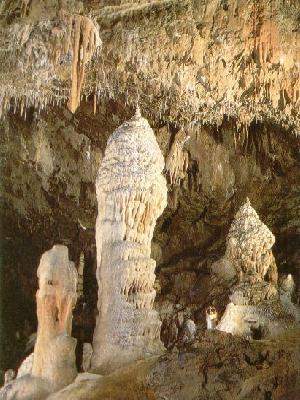

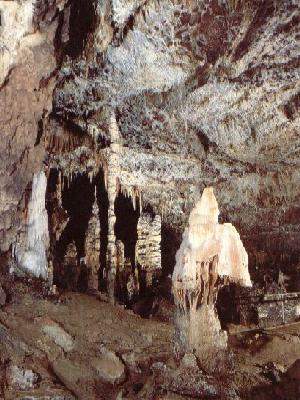

In the course

of karstification, the precipitation becomes acidic from the

carbon-dioxide dissolved by water from the ground. As the acid

water infiltrates the crevices in the limestone, it dilutes them

and thereby the way for the quartz pebbles to be washed down by

the rain into the underground fissures. The pebbles polish the

inner surface while calcium carbonate precipitates from the water

slowly dripping through the hair-line crevices, creating a rich

layer calcium-carbonate dripstone formations on the walls and

floor of the evolving caves. The stalactites and stalagmites,

coloured by multifarious minerals washed underground by the

rainwater, together with dripstone columns, draperies, thin hay

dripstones, coralloids and coral-like formations, helictites,

curves dripstones and rimstone terraces glittering with calcite

crystals, constitute a uniquely rich underground treasure-trove.

Altogether,

there are more than 700 caves known to exist on the Aggtelek

Karst and the Slovak Karst, which together form an integral whole

by virtue geological and geographical features. Among them, one

can equally discover large, horizontal with an active brook and

deep almost vertical shafts in the north-eastern parts of the

national park. Their treasures have been included in the World

Heritage List. Here shall stand only a few rapturous lines from

the Canadian geologist Lloyd Trevor about their enchanting

impression of theses miraculous caves:

“In the

course of my entire tour of Europe, obtained the deepest and most

lasting impressions when visiting your Aggtelek Cave… It is not

only the scientific significance of your cave that is

immeasurable, but the gigantic horizons of its underground

cavities and the enthralling mass of the crystal formations that

make even the lay visitor come to realise that this unparalleled

masterpiece of nature has been called to existence by the very

same geological forces and processes that still play a major role

in developing the crust of earth.”

A group of student near the entrance of the Baradla Cave - By Aranyi Laci

The Aggtelek

National Park, thanks to its geographical position and geological

structure, has very special climatic and hydrological conditions.

The amount of precipitation falls short of the average of medium

elevation hills; this is because the area is surrounded by higher

hills and mountains on all sides. The annual mean temperature of

the region is 10

°C, and the daily figures are below the

national average. In deeper valleys (in the period when deciduous

trees have their foliage( and in the caves, the level of air

humidity can approach 100%. A special characteristic of the

region’s clear air is that the pollen of several plants causing

allergic symptoms, cannot be found in the Park’s area.

The most

important characteristics of the flora and fauna of the Aggtelek

Karst are their marginal position and transitory character. In

terms of phyto-geography it belongs to an independent floral

district that has evolved under karst conditions at the

overlapping of Carpathian and Pannonian floral sectors. The

enormous wealth in species and habitats that this mostly forested

area possesses in indicated by a series of species with a wide

range of ecological needs and characteristics.

One of the

most characteristic forest communities of the karst land is the

mixed hornbeam-oak wood, which provides a general basis for the

numerous flora and fauna association. One can find several steppe

and wooded steppe species in the warmth-loving oak forest lying

on southern slopes, and there are sub-Mediterranean and middle

eastern species in Downy Oak dominated karst scrub forests and in

rock grasslands. This is the only place on earth where the

International Red Book species íof the Tornaian Golden Drop can

be found, which naturally enjoys strict protection, and the only

Hungarian sites of the Austrian Dragonhead are here.

The

mosaic-like communities of scrub forest and rock grasslands

treasure a spectacularly rich fauna. Especially, the orders of

butterflies and Orthopterans (grasshoppers, crickets) are

represented here by rare species. The invertebrates of these

multicoloured and flower-rich grasslands include a large

grasshopper, Saga pedo, and Clouded Apollo butterflies. Tiny

Snake-eyed Skinks and more corpulent Green Lizards lurk in the

crevices of rocky outcrops that divide wind-ruffled fields of

Feather-grass. The beautiful scarlet Pyramidal Orchid represents

the orchid family in the secondary hillside meadows, while in

autumn one is bound to witness the blooming of various blue

Gentian species.

The stream

valleys dividing the karst land are garlanded by pretty resinous

alder groves. A rare amphibian of the cool, shady stream valleys

is the Fire salamander that is the logo of the Aggtelek National

Park. The cross bog meadows with Cotton-grass and wet meadows are

a riot of colour in the lower river sections.

A group of student next to the exit of the Baradla Cave, just in the Hungarian-Slovakian national border - by Aranyi Laci

A Europe-wide

rare nesting bird of tall sedges is the Corncrake. The national

park gives home to the largest Hungarian population of the Hazel

Hen, the only grouse native to Hungary. Here is the nesting place

of the rarest breeding songbird of the country, the Dipper, and

the Imperial Eagle also broods in this area. The most frequent

bird of prey is the Common Buzzard. In the past decade several

large predators, that were once native to this region, such as

the Wolf and the Lynx have resettled in the national park. oMan has been constantly present

in the territory of the Aggtelek karst since prehistoric age. The

extensive forest teeming with game animals attracted hunting

tribes and the cultivation of land began in the Neolithic period.

The tools and remnants of the artistic line-decorated earthware

of the Bükk culture were found in large numbers at Aggtelek.

Archaeologists also unearthed several fine, thin-walled ceramic

items ornamented by bundles of lines. The late Bronze Age and the

early Iron Age are represented by golden bracelets, rings and

bright black bowl fragments. Some pottery has also remained from

the Roman Age.

The

settlements of the region were established in the Middle Ages. As

soon as the Tartar invasion ended, the reconstruction work began.

Not only churches were erected by the hundreds in the country,

but monasteries were also established one after the other. At a

distance of only about an hour’s walk from the Martonyi

settlement, there are the ruins of a Pauline cloister, founded in

1947, but now overgrown by vegetation. The round church in

Szalonna, dating from the time of the Árpád dynasty, is worth

visiting for the fragmented frescos on its inside walls, and the

Romanesque church in Rakacaszend, with the straight back wall of

its chancel is also noted for its precious fresco fragments and

painted wooden ceiling dating from 1657. The twin-chancel Roman

Catholic church in Tornaszentandrás in unique among Hungarian

protected monuments.

The 13th

century Protestant church, since the rebuilt several times

furnishes an impressive view with its sunk panel ceiling, wooden

shingle roof and wooden belfry. The Romanesque church in Ragály

is much simpler, but its not, without a spire, has stood in its

place virtually unaltered since the 13th

century. The painted sunk panel ceilings of the Jósvafő and

Tornakápolna churches are valuable pieces of art dating from the

18th century. The pieces of wooden

furniture (e.g. benches, pulpits and ceilings) in the above

mentioned churches and products of master painters belong to the

most beautiful relics of Hungarian folk ornamentation. One can

also discover cemeteries with beautiful wooden grave-pots at

peripheral villages in the Aggtelek karst, namely in Aggtelek,

Teresznye and Jósvafő.

Similarly to

the other regions of the country, castles were built one after

the other in the second half of the 13th

century in north-eastern Hungary. To the north of the Szögliget

settlement, the Szád Castle was erected on Szárd Hill in the

1250’s by the command of King Béla IV in defence of his domain

in Torna. This castle was reckoned to be one of the largest

Hungarian castles at that time. In the garden of the Baroque

castle in a protected park in Tornanádaska, a 15th

century well from Venice can be seen, equipped with an iron winch

structure. The building presently as an institution for the

handicapped. The medieval settlements surrounding the territory proper of the national park stretch out along a valley or along a road, and predominantly have a longitudinal structure dominated by one main street. The bulk of their dwelling houses were built at the turn of the century or afterwards. The region has retained its natural, historical and cultural heritage almost intact, accompanied be elements of traditional peasant agriculture. Visitors of the Aggtelek National

Park are offered a rich programme during any season. The

Baradla-Domica cave system is an outstanding sight which can be

visited throughout the year with guided tours of different length

and difficulty. The alternatives range from ground tours (village

walks, eco tours, botanical tours), ornithological trips, visits

to Hucul stud (kept for the purpose of genetic preservation) and

horse riding excursions to the cultural highlights of the

villages nearby. Student groups can participate in all tours

organised by the National Park with a 50% reduction in price.

Among the numerous programmes organised for tourists and among

cultural events in general, the annual series of cave concerts

stands out vividly. Guests wishing to have a profound rest and

perfect relaxation are most cordially welcomed by the various

accommodation facilities operated by the park management, like

the Baradla Tourist Hotel and Camping in Aggtelek, and the Hotel

Tengerszem (Hotel Tarn) in Jósvafő, as well as by the cheap

pensions and tourist houses in the surrounding settlements.

The caves of the

Aggtelek Karst

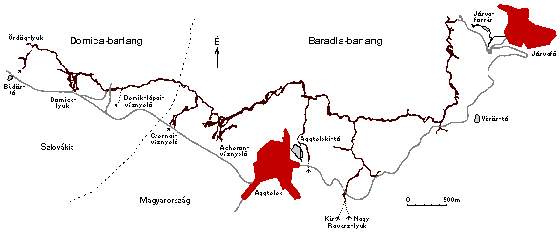

The

Map of Baradla Cave

The

list of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage sites

includes numerous caves, mostly designated because of their

cultural-historic value. Caves as natural formations have so far

only acquired World Heritage status in four cases. After a joint

application by Hungary and Slovakia, UNESCO’s World Heritage

Committee included the caves of the Aggtelek Karst and the Slovak

Karst in its list of the world’s most treasured natural assets

at its meeting held in Berlin, in December 1995. The Mammoth Cave

(USA, Kentucky) with an extension of 560 km below surface, and

registered as the world’s longest cave, was first included in

the list in 1981. Following this, in 1986, the Skocjani Cave

(Slovenia), which forms a subterranean riverbed with the

world’s highest water output, was put on the list. Finally, in

1995 – at the summer time as the caves of the Aggtelek and

Slovak Karst – the caves of the Carlsbad National Park (USA)

were included, and among its numerous caves – along with its

name-giving cavern – there is a cave, which is considered the

most beautiful in the world.

The

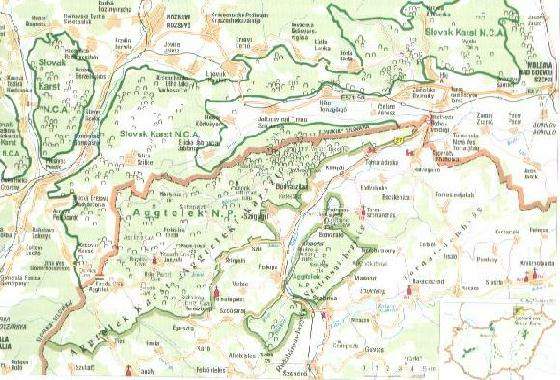

area of Aggtelek and Slovak Karst (once called the Gömör-Torna

Karst) is divided by the Slovak-Hungarian state border,

nevertheless it forms an integral unit not only geographically,

geologically hydrologically and ecologically, but also from the

point of view of cultural history, and more than 700 hundred

caves are known there. This subterrain world of diverse origin

embodies one of the most complex sets of temperate karst

formations yet discovered in mountains of medium height. With its

abundance of forms versatility of speleothems, unique fauna, as

well as its archaeological and historical relicts, this

underground world proudly occupies a place in the first category

of the Natural Heritage list.

Of

the caves classified as a World Heritage site, 280 lie beneath

the surface of today’s Hungary. This figure constitutes

approximately 8% of the more than 3500 registered caves. The

length of seventeen caves exceeds 200 metres, and eight caves are

over 1000 metres long. Fifteen caves stretch more than 50 metres

below the surface, and six descend beyond 100 metres. This is

where Hungary’s longest and third longest caves are situated.

The length of the Baradla-Domica system is put a 25 km, and that

of the Béke (Peace) Cave at 7.2 km. The estimated length of the

latter is expected to increase in the near future as a result of

recent exploration. Hungary’s second deepest cave, the

Vecsem-Bükk Shaft which has a spectacular entrance and has been

explored to a depth of 236 metres, is also located in the

Aggtelek Karst right on the Slovakian border.

A lonely one - by Aranyi

Laci

The

most famous caves at Aggtelek are those with origins, which can

be traced back to streams. The dissolving formed these caves and

polishing effect of watercourses wove their way below the hills

via swallets. Many of theses, such as the Béke and Kossuth

Caves, have water streaming in them the whole year round,

however, there are also caves in which water only enters after

winter snows have thawed or after heavy rains. Caves with such

temporary activity include the Meteor, Szabadság

(Liberty) and

Vass Imre Caves. In the southern, lower-lying parts of the karst

region, the nearly horizontal caves with streams and shorter or

longer tributaries joining the main stream, are typical. In

upland areas the water, which flows underground through

seasonally active swallets, forms steep caves with a gradual and

vertical shafts divide ‘step-by-step’ decline and which.

However, the vast majority of this type of cave has become

inactive due to karst activities, so the channels in them were

filled with sediment.

Another

major cave type includes the vertical system that is presumed to

have developed as a corollary of the dissolving effect of waters

seeping through surface cracks. This type of cave is typical of

the region’s karst plateau. Within this type there are 64 caves

belonging to a sub-class characterized by parallel shafts. These

shafts, whose walls could be likened to those of a well, are

concentrated

in the area of Alsó-hegy (Lower Hill) where they appear in

unique density. Around d a third of the known caves here are

located within half a square kilometre. 22 that have been formed by ascending waters complement the diversity of cave types. Theses are thought to have been created by the dissolving effect produced when warm and lukewarm waters mixed together in the limestone block of the Esztramos Hill. This giant block is located in the Szalonna Karst to the south/east of the main karst region.

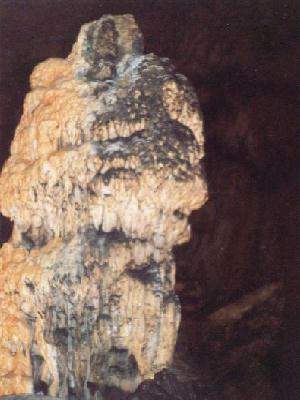

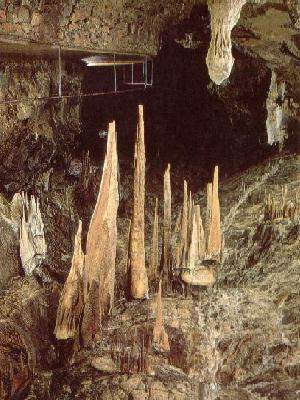

A group of Dripstones - in a

picture postcard The caves also contain numerous spectacular mineral deposits, the

most common being calcite and aragonite, along with gypsum and temporarily

appearing ice-formation. So far, 20, of the 25 existing basic types of carbonate

speleothems have been identified, a fact regarded by the international

scientific community as a real rarity. The most common forms are the

stalagmites, stalactites, draperies and flowstones, all which vary in shape,

size and colour, and often cover large surfaces. Rimstone dams, pools and cave

pearls, which are linked to dripping or flowing water, are also frequent.

Likewise, aragonite bushes, popcorn-ícoralloids, helicties, cave rafts, moonmilk,

cave shields and shelfstone resulting from seeping and stagnant waters, can be

found. The coralloids in the Rákóczi

Cave, registered within the

international scientific literature summing up minerals of the world, are said

to be one of the world’s best displays of the type.

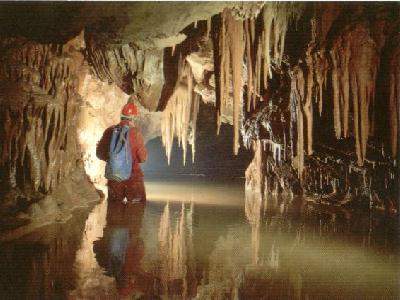

The Baradla-Domica cave takes the most

prestigious place among the caves registered as world heritage being the longest

temperate climate cave that contains an active stream and is richly decorated by

dripstones. Domica is the 5.6 km long section of this multi-entrance system that

extends below Slovakia. Baradla, which in the last century was considered to be

the second longest cave in the world, was ranked eighth in 1965, fourteenth in

1969 and twentieth in 1973. Today, it unfortunately does not even rank amongst

the 100 longest cave in the world. However, in the temperate zone, none of the

active stream caves that are longer than Baradla contain such a wealth of

speleothems. The first written document, which – although with the wrong

determination of position – mentions the Baradla Cave’s petrified dripping,

dates from 1549, and the first Hungarian language description appears in a

schoolbook written in 1788. Since the end of the 18th century the

cave has attracted many scientists from abroad who published their findings. The

Englishman Townson visited the site as early as 1794, Hunter soon after in 1799,

with the Pole Staszic following in his footsteps in the same year, the Russian

Glinka visited Baradla in 1808, and the Frenchman Beudant arrived in 1818. The

cave’s first sketch map, drawn by the Hungarian Sartory

József, is regarded in international literature as the first map of a cave

worked out by an engineer. After Vass Imre discovered an extension to Baradla in

1825, it became the world’s longest charted cave of the time. Baradla was also

one of the very first caves to be opened to tourists. There were organized tours

to the cave at the beginning or the 18th century, and in 1806 – to

ease wandering – bridges, steps and footpaths were constructed, and when

high-ranking guests paid a visit the cavern was even furnished with candles to

illuminate the way. A connection between the Baradla and Domica caves was

predicted as early as 1801 and finally proved in 1932.

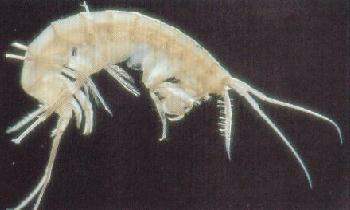

The Aggtelek Well Shrimp is

a characteristic inhabitant of the underground waters of the

Aggtelek Karst.

The

cave’s 7 km long main branch, which stretches from Aggtelek to

Jósvafő, is the bed of a subterranean stream. The rock tunnel

is on average 10 m wide, 7-8 high and widens into enormous

chambers at several points, and auxiliary branches join the

principal passage. The channels are decorated by ornate

stalagmites and stalactites of various colors and shapes which

appearing on mass offer a spectacular view with fantasy-moving

forms, huge sizes and gleaming colors. The largest stalagmite,

called the Observatory, is some 18 m high. Nowadays, the stream

only flow through the entire length of the main branch in times

of flood, and it sinks via swallets into Lower Caves, which lie

30-40 m deeper. Two independent lower caves are now known to lie

below Baradla. Cavers have succeeded in penetrating along a 1 km

long section of the so-called Short Lower Cave after having

pumped out the water.

Among the large active stream caves of the temperate zone, the richness of dripstones in Baradla Cave is unmatched - in a picture postcard

The

caves of the Aggtelek Karst are also precious for their wildlife,

since they provide habitat to over 500 animal species, some of

which are visitors whilst other live permanently in the caves.

Some species are endemic and were first described here.

Biological research at Baradla began in the 19th

century. The Hungarian Dudich Endre - the founder of modern cave

biology – conducted the first in-depth research, which took

into account the physical attributes of the cave habitats. In his

monograph, published in Vienna in 1932, he described 262 species

occurring in Baradla, an announcement unparalleled at the time in

Europe. In the Fox Branch, one of the cave’s offshoots. Dudich

Endre maintained a specially equipped biological laboratory from

1958. Research carried out in the caves of Aggtelek Karst has

shed light on approximately 500 cave-dwelling (troglobiont)

species invertebrate species and sub-species, as well as on

species that occur in cave-like (troglofile) habitats. A total of

38 species proved to be new and 35 species were first identified

here in Hungary. The species of Duvalius Hungaricus, which is of

outstanding importance, can be found only in the caves of the

Aggtelek and Slovak Karst. Typical cave-dwelling invertebrate

here include Mesonicus graniger, the Aggtelek Well Shrimp, which

often appears in springs and wells, and worm species whose one

and only known habitat is Baradla’s short Lower Cave.

Dripstones with a stream - by Kádasi Adrienn 5a

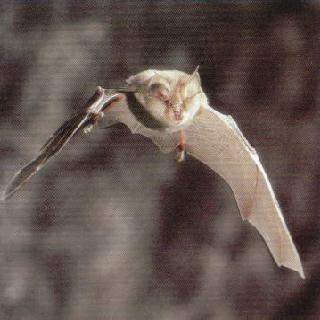

Bats

(trogloxene species) are arguably the most important

representatives of species that spend only certain periods of

their lives in caves. Of the 30 European bat species, 21 have

been recorded in this area. Besides the two species registered as

vulnerable in the 1994 IUCN (International Union for Conserving

Nature) Red List, namely the Pond Bat and the Greater Mouse-eared

Bat, the colony of around 1500 specimens of Mediterranean

Horseshoe Bat, which winters in the Baradla-Domica cave system,

is European significance.

Groups of wonderful

dripstones - in a picture postcard The

World Heritage listed of the Aggtelek Karst are also important as

geological sites since their passages and channels facilitate the

study – to otherwise inaccessible depths and over large

surfaces – of the various types of limestone and fossil remains

from the sea that covered the area in the Triassic Period. In the

main branch of the Baradla Cave, seven wall sections,

constituting the most representative of the explored sites, have

been classified as geological key profiles. Indeed, these are the

world’s only geological key sections to have been explored in a

cave. Sediments that have accumulated in the smaller caves,

crevices and paleo-karst cavities are rich in fossil remains of

vertebrate species with ages ranging from the middle Pliocene to

the late Pleistocene era. Findings in the Eszramos Hill are of

special significance as these have provided essential data on the

stratigraphical division of geological history. The

internationally recognized middle Pliocene bio-stratigraphic

stage in the development of vertebrates, ’Estramontinum’

acquired its name from this location. The excavation site No. 7

is an international reference site of findings indicating the

boundary between the Pliocene and the Pleistocene layers. Archaeological evidence has shown that in the pre-historic times man knew some of the caves that have been classified as a World heritage site. The Baradla Cave is on of the most well-known prehistoric excavation sites in Hungary with the first excavation conducted here in 1876. A large number of findings – have been found in the passage of the main entrance of the cave and in its adjacent chambers. The cave opens up near Aggtelek at the foot of a 50 m high rock, which appears glittering white when seen from afar. Among theses findings depicting the so called Neolithic Bükk culture (5000-3000) years BC) there are the traces of posts from earlier cottages, remnants of fireplaces, a great quantity of debris, as well as numerous intact ceramics, which were produced without a popper’s wheel and enamelled with parallel lines. Certain signs attest to the fact that following this; the cave was uninhabited for quite some time, since subsequent findings only date back to the late Bronze Age. The hypothesis of archaeologists suggest that in the Neolithic Age the cave was used as winter dwellings and a source of water, whereas in the late Bronze Age as a burial and possibly worship place. The caves, particularly the Baradla, have many times provided refuge to our forebearers from historic times, until more recent times.

Aggtelek’s

World Heritage caves are outstanding underground museums and

on-site laboratories for the natural sciences research carried

out in this region has played a major role in the development of

the natural sciences, since the caves and their formations are

still in a state of continual change and thus provide an

excellent opportunity to study subterranean processes and the

surface phenomena which influence them. The Jósvafő Karst

Research Station was the first in the world to show, by means of

continuous measurement, how the tidal phenomenon affects the

fluctuation of the water output of karst springs. Studies at the

Lófej (Horsehead) and Nagy-Tohonya springs have made its

possible to construct a model of complex siphon effects. The

result of hydrological research point to the existence of tens

kilometres of as yet unexplored cave channels. This provides for

further excavation, especially in Baradla’s Long Lower cave, as

well as in Kossuth. Vass Imre and Meteor caves.

Stalagtits and stalagmits -

in a picture postcard

Guided

tours of different character and level of difficulty enable

visitors to experience the treasures of theses museums created by

nature which are registered as World Heritage sites. Nearly

200,000 people visit the opened caves annually, with many

visitors arriving from different countries of Europe and other

continents.

Besides

their importance as scientific research and centres of education,

the caves have other practical benefits, too. Several of the

settlements in the karst region are supplied with drinking water

from the springs of active, water-carrying caves. The

particularly clean and invigorating air of the Béke Cave, the

first in Hungary to be declared a therapeutic cave, has been a

centre for curing respiratory disorders for three decades. The

process of declaring the Baradla Cave a therapeutic cave is also

underway.

According

to the regulations of the World Heritage Treaty only those most

outstanding natural treasuries are to be included in the list,

and which are relatively intact whose protection can be

guaranteed. The caves of the Aggtelek Karst meet this set of

criteria, since the vast majority of them can be considered to be

in a prestine state. This is due to the fact that most of them

were only discovered over the last few decades.

AGGTELEK

Clear mountain brooks

provide a habitat fot the Dipper.

A village of

Hungary, in the county of Gömör, situated to the south of

Rozsnyó, on the road from Budapest to Dobsina. In the

neighbourhood is the celebrated Aggtelek or Baradla cavern, one

of the largest and most remarkable stalactite grottos in Europe.

It has a length, together with its ramifications, of over 5

miles, and is formed of two caverns — one known for several

centuries, and another discovered by the naturalist Adolf Schmidl

in 1856. Two entrances give access to the grotto, an old one

extremely narrow, and a new one, made in 1890, through which the

exploration of the cavern can be made in about 8 hours, half the

time it took before. The cavern is composed of a 1'abyrinth of

passages and large and small halls, and is traversed by a stream.

In these caverns there are numerous stalactite structures, which,

from their curious and fantastic shapes, have received such names

as the Image of the Virgin, the Mosaic Altar, &c. The

principal parts are the Paradises with the finest stalactites,

the Astronomical Tower and the Beinhaus. Rats, frogs and bats

form actually the only animal life in the caves, but a great

number of antediluvian animal bones have been found here, as well

as human bones and numerous remains of prehistoric human

settlements.

Finely

scalliped Flowstone can be seen in several caves of the Aggtelek

Karst.

Aggtelek National Park Directorate Address: H -

3758 Jósvafő, Tengerszem oldal 1.

|

|